December 26, 1908. It was time for the start of the long awaited world heavyweight championship fight between the holder, Tommy Burns, and Jack Johnson. Johnson, however, was flatly refusing to go into the ring unless he received more money. Grabbing a revolver, promoter Hugh D. McIntosh, burst into his dressing room.

December 26, 1908. It was time for the start of the long awaited world heavyweight championship fight between the holder, Tommy Burns, and Jack Johnson. Johnson, however, was flatly refusing to go into the ring unless he received more money. Grabbing a revolver, promoter Hugh D. McIntosh, burst into his dressing room.“If you’re not in the ring in two minutes,” he snarled, “I’ll blow your brains all over the floor.” Johnson rose with alacrity, his gold teeth flashing as he grinned, “Massa Mac, Ah’m on mah way.” It would have taken a shrewder man than Johnson to get the better of Hugh D. McIntosh.

Hard as nails and cunning as a fox, the bull knecked Hugh D. McIntosh, was an entrepreneurial genius. His father, a local police sergeant, was unimpressed when at the age of ten, young Hugh told him that he was going to make his fortune, and that he didn’t care how he did it. It was a philosophy that stayed with him as he made and lost several fortunes over four decades of wheeling and dealing.

A millionaire by his early thirties, “Huge Deal,” as he was aptly known, had a diverse career. Starting with a basket of pies, he became a successful restaurateur, newspaper proprietor, theatre magnate and politician. He was responsible for pulling cycling out of the mud, attracting crowds of upto fifty thousand - and always a man of style - was the first to introduce china cups to the top of Mount Kosciusko.

It was McIntosh’s vision and flair, that made Sydney Stadium possible. With the artfulness that was the hallmark of his career, he succeeded where the world’s top promoters had failed. He enticed Tommy Burns to put his world heavyweight title on the line against the gigantic Negro, Jack Johnson.

Johnson stepped into the ring and into the history books, as the first colored heavyweight champion of the world. With the world’s press, and writers such as Jack London and Damon Runyan, covering what was as much a battle of the races, as a title fight, Sydney and the open air stadium at Rushcutters Bay, became famous the world over.

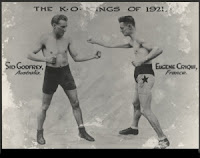

McIntosh promoted some of the greatest fights ever seen in Australia. Fights, which during Australia’s Federal infancy, put the fledgling commonwealth on the sporting map of the globe. The world’s top fighters flocked to Australia, and Sydney Stadium became a Mecca for the pride of the American and European rings.

Hugh Donald McIntosh was born in 1876 in a tiny house at the bottom of Sydney’s Macquarie Street. After revealing his ambition to his father, and discovering that they did not see eye to eye on business matters, McIntosh left home. As many people would later discover, McIntosh was not one to let anybody stand in his way.

He became an assistant to a travelling tinker and for two years they wandered throughout NSW. Eventually McIntosh deserted him in Broken Hill, taking a more profitable job picking silver ore.

However, the back breaking work was not to his liking. He decided that it was better to work with his brain, than with his back. He drifted to Melbourne, where for a while he played the hind legs of a mule in pantomime. Returning to Sydney at the beginning of the booming 1890s, he became a bread carter. It was to be the last time he would work for someone else.

McIntosh set up in business as a pieman. He started with virtually nothing except a basket and six dozen pies bought on credit from a Redfern factory. Within a few months, he had an army of white coated vendors thronging Sydney’s racecourses, beaches and parks - “coining,” money for him.

No opening was ignored. He even sent his piemen knocking on the doors of the illicit two-up schools, betting clubs and houses of ill repute, that dotted Surrey Hills, Darlinghurst and Wooloomooloo. With the profits, McIntosh set up his own factory at North Sydney. From there it was an easy graduation to ownership of a chain of plush, ornate restaurants.

Always on the lookout for money making opportunities, McIntosh set his sights on cycle racing, which was then the most popular sport of the day. With his flair for showmanship and the ability if necessary to control trouble making cyclists with a spanner, McIntosh had no difficulty in making himself the king-pin cycling promoter. When the cycling boom ended, Hugh D. sought out other lucrative ventures.

I

n 1908, the Prime Minister, Mr. Alfred Deakin, orchestrated a goodwill visit of 16 warships of the US Navy. It was the impending arrival of The 'Great White Fleet', that planted in McIntosh’s mind, the seed that would grow into Sydney Stadium.

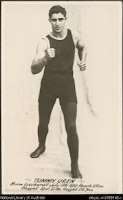

n 1908, the Prime Minister, Mr. Alfred Deakin, orchestrated a goodwill visit of 16 warships of the US Navy. It was the impending arrival of The 'Great White Fleet', that planted in McIntosh’s mind, the seed that would grow into Sydney Stadium.He had for some time thought of bringing world heavyweight champion Tommy Burns to Australia. McIntosh believed that the 12,000 American sailors would pay good money to see a world title fight. Forming a company called the Scientific Boxing and Self Defense Ltd., McIntosh cabled Burns an offer of £4000, to defend his title against the slogging Australian miner, Bill Squires.

With the contest arranged, Hugh D. now had to find somewhere to stage it. He initially chose the Exhibition Building, which was situated in Prince Alfred Park, near the Railway Station. However, when he went to view it, McIntosh found barriers erected. and a large man, making unmistakable signs with his huge fingers. McIntosh decided to seek out an alternative venue.

He wandered down to Rushcutters Bay in an old shabby suit selected for the occasion, and gazed over a waste where once a Chinese market garden had bloomed. While he looked and nosed around, the owner approached him and asked McIntosh what he wanted.

McIntosh looked sadly at the site of the garden. He told him he was looking for a place to put up a nice two man show with a view to making a bob or two during Fleet Week. After some negotiation, McIntosh agreed to rent the land. The rent was £2 per week for two years, with the right to renewal for the same term at £4 per week!

A few days later the owner was astounded to see vast piles of building material being dumped on the land. When he made inquiries he was taken to the man he had met in patched pants, but who was now resplendent in an expensive suit. “Huge Deal” handed him a cigar and said, “It’s for my two man show - the Burns - Squires fight.”

At a cost of £2000, McIntosh quickly erected a huge unroofed timber stadium, that was destined to become, “The Old Tin Shed.”

The fight was a huge success, but not because of the American Sailors. They stayed away in thousands. It is said that only two sailors were present and both were drunk, staggering down to the ring, offering to fight anybody for two dollars. Twenty thousand Sydneysiders, however, paid the unprecedented gate of £13,600 to see Burns win easily.

The success of that fight spurred him to renew his lease and stage the biggest boxing match in Australian history.

For years Jack Johnson had been trying to get into a ring with Tommy Burns, but the champion had persistently dodged him. McIntosh asked Burns what he would want to meet Johnson. Believing that McIntosh would never pay it, Burns demanded £6000. The Australian promoter accepted on the spot and Tommy was trapped.

For years Jack Johnson had been trying to get into a ring with Tommy Burns, but the champion had persistently dodged him. McIntosh asked Burns what he would want to meet Johnson. Believing that McIntosh would never pay it, Burns demanded £6000. The Australian promoter accepted on the spot and Tommy was trapped.The jubilant Johnson was satisfied with £1000 as his payment, (later raised to £1500), and the fight was on.

For Burns it was the end of the road. It is now ring history how Johnson cruelly and methodically carved him to pieces, and won the title that he was to hold for the next seven years.

With ringside seats at £10, McIntosh made his greatest financial killing. The gate receipts were £26000, then a world record. From these boxing promotions and others over the next few years, Hugh D. McIntosh raked in more than a quarter million pounds.

McIntosh went to England and America and made a name for himself in London as a fight promoter. When he returned to Australia, he was followed by a crowd of the world’s best boxing talent.

Boxing was lifted to a high level. The only thing that prevented it being completely respectable was the “Fear of The Dark”. McIntosh introduced a stream of colored fighters to the white boxing world, helping to make heavyweights like Sam Langford and Sam McVea world famous.

Until McIntosh, promoters believed there was little money to be made by putting two colored fighters in the same ring. However, Australia gazed with mingled awe and delight at the spectacle of McVea and Langford knocking corners of each other.

It was also under his management that Jimmy Clabby, Billy Papke, Cyclone Johnny Thompson and a team of French boxers, descended on Sydney and Australia.

McIntosh decided to expand. The first thing was to put a roof over the Stadium. The arena was entirely transformed. From having an exterior consisting of hideous poster hoarding, it became an elegant castellated structure. Solid concrete foundations were put in to support the weight of the roof and when it was finished, it was possible to have boxing, or any other sport there all the year round. On August 3rd, 1912, Sam Langford outpointed Sam McVea, in the first fight held under cover.

Later that year, McIntosh thought it was time to develop the more artistic side of his entrepreneurial genius. One morning, Sydneysiders awoke and learned with amazement that Hugh D. McIntosh had paid £100,000 to take over the huge Rickards theatre circuit.

For a brief while he ran both establishments, but on December 2nd 1912, the Stadium was taken over on approval by Reginald (Snowy) L. Baker. In March 1913, he bought the business lock, stock and barrel and Hugh D. McIntosh ceased to have any but sentimental interest in the great stadium he had created.

McIntosh began to live the role of the successful tycoon, buying a mansion, “Bellhaven,” at Bellevue Hill and a fleet of Pierce-Arrow cars with his crest prominently displayed on the doors.

A personal friend of the Premier, W.A. Holman, he was elected to a seat in the NSW Legislative Council, which he held till he was made bankrupt in 1932.

Hugh D. entertained on a fabulous scale. Many visiting celebrities, enjoyed his hospitality. He made his money easily and he squandered it the same way. His gifts of motor cars to friends, diamond studded wrist watches to chorus girls and gold cigarette cases to mere acquaintances, became the talk of the town.

Hankering for fresh fields, McIntosh now bought the Sydney Sunday Times the oldest Sunday newspaper in Australia. It was a vehicle he would later use to persecute the great Les Darcy.

McIntosh had his own ideas on how to increase circulation. One such example was an offer to a notorious murderer named Simpson on the eve of his execution. Simpson would be paid £5000, if he would endeavor to come back from the dead and appear at the Sunday Times office before witnesses.

Visited in his cell, Simpson accepted the proposition eagerly. He jotted down the address of the newspaper office, so he would not “get lost on the way,” and promised to do his best to solve “the age old riddle of whether the dead could return.” Forty people gathered in McIntosh’s office on the night following Simpson’s execution. Simpson, however, was not one of them.

By such stunts, McIntosh did more harm than good to the paper, which had previously enjoyed a valuable prestige. It became one of his financial failures.

In 1928 Hugh D. McIntosh tried his luck in England. He bought Broome Park, a seventeenth century mansion set in 600 acres and formerly owned by Lord Kitchener.

In association with C.B. Cochran, he promoted a few fights in the Olympia Annex in London and also at stadiums in Paris. None of them earned enough to keep him in cigars.

For four years, McIntosh lived a fantastic round of pleasure in England. He poured out his money entertaining the rich, the famous, the titled, and beggared himself in the process.

In 1932 he returned to Australia broke. Bankruptcy proceedings were instituted against him. His liabilities were proved at a staggering figure.

But Hugh D. McIntosh could not be kept down for long. He was soon staging a comeback, promoting fights at the Sydney Stadium. Full of enthusiasm, he imported the American heavyweight Young Stribling and matched him with the Australian heavyweight Ambrose Palmer, hoping to repeat his 1908 clean up with Burns and Johnson.

It was not to be. The takings amounted to only £3800 and Stribling alone had been guaranteed £3000. Another financial body blow followed with the failure of a boomed match between Ron Richards and Fred Henneberry.

The now aging promoter was down - but he was not out. He threw himself into the flotation of a chain of cake shops and opened a large guest house in the Blue Mountains.

In 1935 he sailed once more for England, where on August 1 he opened what was to be the first of a chain of 500 McIntosh milk bars throughout the country.

With an excess of ballyhoo, a company was floated which McIntosh said would soon be disposing of the milk output of a million cows, to two million customers a week.

McIntosh opened a dozen milk bars in London, and it seemed he was on the right foot again. However, lack of capital and cut-throat competition beat him.

When he died in 1942, he was penniless. His old time friends had to contribute to a fund to defray his funeral expenses.

Copyright Mike Hitchen, Lane Cove, NSW, Australia. All rights reserved